Interviews with experts and opinion leaders from our research network

While the people referred to as geniuses found throughout the history of science stood upon mountains of accumulated knowledge produced by their predecessors, they possessed extensive curiosity and strong levels of enthusiasm. These geniuses came up with revolutionary ideas while maintaining attitudes whereby they did not bound themselves to preconceived ideas, thus generating great achievements, or innovations, that are still well-known parts of the history of science even today. For this interview, we have invited science writer Dr. Kaoru Takeuchi to speak with us. He is well-versed in the history of science and has been active in a wide range of fields as a science communicator. He is also working to tackle issues having to do with education. Today, we’re going to think about what human resource development should look like in the age of artificial intelligence. We will touch on elements like the process of sparking innovation, as well as the importance of inquiry-based education that is not bound by a framework which divides everything up into the humanities and the sciences, meaning areas where we in the modern era should be learning from the geniuses found throughout the history of science. (The interviewer is Osamu Naito, Former Chairman of Hitachi Research Institute)

Science Writer

Born in Tokyo in 1960. Holding two bachelor’s degrees from the University of Tokyo; the Department of Arts and Sciences at the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Department of Physics, Faculty of Science. In 1992, he received a PhD at McGill University, becoming a Doctor of Science specialized in high energy physics. After finishing graduate school, he started working as a science writer. He has written more than 150 works, which are comprised mainly of physics manuals and works involving scientific commentary.

He is widely known as a science communicator. He has provided commentary on the show Takeshi Kitano Presents Comaneci University Mathematics (Fuji TV) and appeared on Science ZERO (NHK E-Tele). He also has a strong interest in education and serves as the Principal of YES International School.

His many works include “99.9% is a Hypothesis” (Kobunsha), “Genius Time” (NTT Publishing), “Not Making Your Child a Slave to AI” (Shinchosha), “Guide to the Great Books of Science by Kaoru Takeuchi” (Tokuma Shoten), “What is Quantum Gravity Theory?,” “What is Superstring Theory?” and “Reading Feynman’s Physics” (3 volumes in total; all published from Kodansha Bluebacks).

Naito:In the past three interviews of the series, we focused on the themes of the Chinese classics, the history of Western philosophy, and the history of Japan in an attempt to learn about the processes which serve to spark innovation. This time around, we speak to the topic of the history of science. When I say the history of science, it does cover a wide range of fields, so I would like to hear your views on three scientists I have chosen based on my own interest—Archimedes*1, Sir Isaac Newton*2, and Mari Curie*3. First, let’s talk about Archimedes. He is known not only for his fundamental achievements in science, such as Archimedes' principle, the calculation of Pi, and the principle of leverage, but also for the anecdotes he left us, such as the one about the construction of an extraordinary weapon in a battle against the Roman army, as well the one about his attempt to engrave a mathematic question on his tombstone. I wanted to know about a more modern assessment of him, so I looked it up. The historian Polybius wrote in one of his history books of the second century B.C. a statement which translates as follows: “A single human brain can be found to be a surprisingly powerful force if given the right place to perform.”*4 Moreover, according to the naturalist Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder), the Roman military commander Marcus Claudius Marcellus, who had highly valued Archimedes' intelligence, issued an order during the siege of Syracuse to the effect that no violence was to be committed against Archimedes*5. In the end, however, the soldiers ran amok and killed him. Although he was curious about everything and was doing research while maintaining an interest in various things, he was very disappointingly killed during the war. But while that was the case, we can see that he was highly appreciated by the enemy nation of Rome.

Takeuchi:My first impression of Archimedes was formed when I heard the story of Archimedes and the Golden Crown during a science experiment at elementary school. To ascertain whether a crown was made of pure gold, he put the same weight of pure gold as the crown into identical containers filled with water. The story goes that the crown was found to be a fake due to the difference in the amount of water which overflowed. That provides the basis of the anecdote about him running through the town naked, shouting “Eureka!” with joy. Although, it seems that this part does not appear in Archimedes' own writings. If this was an anecdote that a later figure had produced based on Archimedes' principle, it would mean that he was a very colorful person. He was aware of his own ignorance, and it was for this reason that he did his best to maintain a stance rooted in the concept that it was not a good thing to give away a source of knowledge to another person*6. It seemed that he was always striving to do his best while maintaining an awareness of his own ignorance. I think that in the end, he only believed what he could contemplate and understand by himself. That would be a difficult thing to replicate in modern Japan, since we have to take in a lot of knowledge due to the nature of the entrance examination system. Even if students think what their teacher has taught them is strange or even when they don’t understand something, they tend to just coast through it all on the premise that what was conveyed has been understood. Archimedes didn’t do that and instead thought things through to the very end.

Naito:It is said that when Archimedes calculated Pi, he sandwiched the outline of a circle between two regular polygons, with one found on the inside and the other on the outside*7, to derive the figure 3.14 by doing calculations for polygons ranging up to a enneacontahexagon (which has 96 sides). This also shows his attitude of pursuing something to the very end, which in a sense, embodies the concepts of philos (love) and sophia (knowledge), or in other words, philosophy (philosophia). At the same time, I think it is a very easy-to-understand way of thinking. Plutarch, a biographer, commented on Archimedes as follows: “When I am unable to find out how to prove something by myself, I feel like I have found it by myself when he shows me the way. When a problem falls into his hands, things get smoothly and quickly directed into the path of being proven.”*8 I think people who can explain difficult theories in easy-to-understand terms are really smart people, and Archimedes was probably just that kind of person about 2,200 years ago. I think that we as well should have the same enthusiasm as Archimedes when it comes to knowledge.

Takeuchi:I think it's wonderful that ancient Greek knowledge is still found in textbooks and that children are learning such knowledge. At my school*9, we also start our classes with thinking about what Pi is. You start by talking about a square where the value of one of its sides is equal to one, then the length of the perimeter is four. Then you ask the kids about what the circumference of a circle inside the square would be, which would be less than four. This way of thinking has been passed down from generation to generation, so obviously, I think that the achievements of ancient people are truly wonderful.

Naito:Archimedes was born in the third century B.C. While there are more storage tools that accumulate knowledge has increased in comparison with then, I believe that our processing power has not changed much since the fifth century B.C. So there is still a lot of room for us to learn from those who lived during ancient times.

Takeuchi:I think that people in the modern world have become able to use computers as external brains. Even something that used to take 10 years to calculated by hand can be calculated in an instant using a computer program. If you take away the development of such a convenient external brain, our fundamental creative abilities might be just the same.

Naito:You mentioned Newton in your works Genius Time and Guide to the Great Books of Science by Kaoru Takeuchi. At the young age of 22 or 23, Newton produced three major achievements: the standardization of calculus, the theory of light, and his law of universal gravitation. It is said that he made all of these discoveries during an 18-month-long creativity break that he took when returning to his native Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth from Cambridge University during an outbreak of the plague. This reminded me of the meaning behind the character 而 (pronounced “shikoshite”) found in the original text*10 of the idiom “Learning the New by Reviewing the Old” (温故知新) that I discussed with Noh performer Noboru Yasuda during a previous interview session. Warming up old knowledge and simmering it in a pot will eventually give rise to new perspectives. In order for that to take place, though, “additional” (here the character 而 is used) time was absolutely required. Hearing that was a real eye-opener. In your book Genius Time, you wrote that humans require a certain amount of time for fermentation. That would be time spent waiting a great deal to allow new knowledge to simmer as opposed to having it pop right out all of a sudden. It could be an hour, it could be a day, it could be 10 years. But at some point, you’ll suddenly have a breakthrough idea come about. I strongly felt that, as you say, such a process is necessary to bring about innovation and that this constitutes the concept of genius time that you’re talking about.

Takeuchi:Newton was a genius and was a giant when it came to knowledge, but I think that he might not have left us with such great achievements had the plague not gone around at the time. I always think about what creativity is. Even if you set a goal and work hard to achieve it, surprisingly, it doesn't always pay off. Sometimes you worry about what to do and have no choice but to take a walk, go on a small trip, or take a long bath. You sometimes need some time to just zone out and not be doing anything. That’s when the human brain is actually doing something behind the scenes. That’s why even if you try your very hardest to get something out there, nothing comes out. However, it’s when you just give up and let your brain do it’s thing, that one day something just pops right out. I think this is a very mysterious state of affairs.

There are characteristic patterns found in the lives of geniuses, whether we’re talking about Newton or Einstein. You could chalk it up to coincidence, but I feel that there is a commonality found between people doing significant things in that they find themselves forced to take a vacation. They continue to take things so seriously for so long that their brains end up piecing everything together when they go on vacation and something positive takes shape at the end of it all.

Naito:It’s not the case that some kind of idea will most definitely come about if you have some free time to spare. And in most cases, nothing does come about. About one or two out of every 10,000 people, maybe even fewer, are able to do this. However, we still have to learn from history when we are thinking about how to create an environment where innovation can occur efficiently. This is even more so the case in the era of COVID-19.

If you look at the historical background of Newton’s time, he was born right in the middle of the Puritan Revolution. When he was a child, Charles I was executed and Oliver Cromwell established the republic. After Cromwell’s death, however, Charles II ascended the throne and the Stuart Restoration took place by the time Newton became a young man. The plague broke out in 1665 and the Great Fire of London happened in 1666. While Newton’s achievements had already been established by this time, James II, who ascended to the throne in 1685, fled to France during the Glorious Revolution.

It was a time of great political instability and many people lost their lives. The execution of the king was a particularly significant event. I think social values were shaken and changed as a result. The situation was similar in Japan after World War II. When the political systems and values of the world have changed drastically, geniuses sometimes appear out of nowhere.

Takeuchi:During the chaos that ensued after World War I, there were important discoveries made by Einstein, the establishment of quantum mechanics, and so on. People who have experienced great upheavals must find themselves stirred emotionally and end up contemplating a lot of things. There is a tendency for geniuses to appear and create human culture as a result of that.

Naito:Newton had been in continued disputes with Robert Hooke and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over his achievements. The story goes that Newton fought with Leibniz for 25 years, and in the end, Leibniz threw his hands up and gave up on the whole situation. If one of the requirements of a genius is to devote oneself to something and to keep doing that thing for a long time, there may be aspects of persistence that go along with it as well.

Newton was competitive in some respects, but he was also blessed with great people around him. One of those people was Isaac Barrow, who was known as the inaugural holder of the prestigious Lucasian Chair of Mathematics*11. He recognized young Newton's talent and named him his successor. And Principia*12 would not have been published without the advice and support of Edmond Halley, the man who calculated the orbit of Halley's Comet. Newton is said to have been a secretive person. Even if he was a genius, he still needed friends, people to collaborate with, and understanding people to support him.

Takeuchi:The surrounding environment is important for genius. I think the reactions of people around a genius are divided into two groups. Some people want to protect the genius and support him or her as a friend, while others want to derail the genius due to their own jealousy. I think there are quite a few geniuses who have been derailed this way in the past. Some of the children I see show remarkable talent in math and art, but surprisingly, the adults around them, including their family members and relatives, are sometimes not aware of that talent. It is very important to find talent and then nurture it.

Naito:In a company, too. I think there are also lots of times when an excellent subordinate employee who is trying to do something original, is derailed by their superior with the excuse “there is no precedent” used against whatever is being proposed. There are some people who manage to survive in this situation somehow and continue to do things that they are told not to do and end up burgeoning into something great. But when we’re looking at things in terms of diversity, I think a spirit of tolerance is probably essential. Something that is often talked about in the business world is whether one has the ability to just let someone get on with what they want to try and achieve as opposed to labelling the person crazy for proposing the idea. Newton survived and was appreciated, but there were probably geniuses in the past who didn’t make it through like he did.

Naito:Let’s talk about Mari Curie. My impression of her is that she continued to fight. She was active in France and was discriminated against because she was Polish and because she was female. Her application to become a member of the French Academy of Sciences was rejected even though she had received the Nobel Prize in Physics. She was later embroiled in a personal scandal, during which she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, meaning a dramatic reversal of events. I'm interested in where her energy to keep fighting came from.

In the world of business administration, “dynamo” have been attracting attention recently. These are people who not only provide their own proposals and plans, but also have the energy to create new businesses, involving others around them. Such people now and then end up getting left out of the situation at hand, so the challenge for managers is how to provide them with support. But given Mari’s environment, she must have dealt with a burden so severe that it could even be considered incredibly unfitting to compare her plight with a situations that take place in a corporate setting.

Takeuchi:When I was in elementary school, I read her autobiography. One part left a great impression on me, which was where she wrote about how she had collapsed after studying too hard. I found myself in awe that a human being can study something to that extent. We usually talk about the concept of persevering. What I felt reading about her experience with perseverance was that I was learning about the ultimate form of perseverance. I wasn’t someone who was able to study until collapsing, so the notion that there are people who really can continue to exert an effort to their extreme limits, is something I found really profound. My image of Marie Curie is more of someone who was a genius when it came to the kind of effort that couldn’t be replicated, as opposed to merely someone who was smart.

I think she worked hard in a lonely environment when looking at things from the perspective of diversity, too. Even though she was from a European country just like those around her, she was said to be faced much discrimination because of which country she was from. Even when we are talking about gender discrimination, it is easily imaginable how difficult it is for women to get on with their lives in a completely male-dominated society, whether they have talent or not. She continued to do her best in such a society. Even with all the barriers she faced, she kept at it until she was recognized by those around her. That really was what made her a genius in my opinion.

Naito:The support activities she conducted during the World War I are similar in that respect. There is a famous story that Mari, who found out that the army had no x-ray facility, went around a field hospital with equipment and a generator installed in a car. People called the car Petit Curie. The one car wasn’t enough by itself, so Mari sought out funding and remodeled it. Apparently, she persuaded the officers to let her continue with her activities despite the military and the administrative organizations expressing their disapproval.

I think there is a lot to be learned from her ability to take action, the energy she had to make the things she believed in come to fruition, and the power she demonstrated. I think it is wonderful that she strongly insisted that the evaluation of scientists should be based on their scientific achievements and not based on where they were from or what their gender was. We must never forget that sentiment.

Takeuchi:We still see remnants of discrimination in the screening of students during the school entrance exam process. When it comes to school entrance examinations, there have been cases, for example, in which quotas on male and female students and passing grade thresholds have been called into question. While things are improving, we need to change things if they do not suit the current situation. I think it is necessary to consider everyone to be on an equal plane, regardless of elements like skin color, differences in economic status and gender, and in some cases, age.

Naito:There was a very energetic female Japanese physicist named Toshiko Yuasa*13. There was a lot of talk about her when she died in Paris in 1980. I was a university student at the time, but I still remember it vividly. After graduating from university, Yuasa read a paper by Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie, the husband of Marie Curie's daughter Irène Joliot-Curie (also a Nobel laureate) and went to France, where she later became a senior researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. After retiring, she became an honorary researcher and was awarded Japan’s Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon.

She studied under Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie and received her degree in 1943. This was just when the war was going on. Yuasa hesitated to go to France in 1940, but her father, who was in poor health, encouraged her to go. After Yuasa heard of her father's death in Paris, Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie told her of the death of Mari's husband Pierre. Yuasa was encouraged by Pierre's words, which were: “Even if I die and become a soul, I will continue with my research.” While I think that things were really hard for people during the war, I think that we must not forget that there were such wonderful female researchers here in Japan as well.

Takeuchi:What worries me right now is that fewer and fewer students are willing to go abroad to study. More and more people seem to think that they can do the same kind of studying here in Japan without having to go abroad. It's true that going abroad can be difficult for many reasons, but there are things you can't do unless you're still young. Actually going abroad allows one to truly get a sense for the diversity and vastness of the world. All experiences are valuable, including being exposed to various cultures, even if you conversely run into experiences that are less than pleasant. I think it’s a pity that more and more people think that they don’t need to go abroad despite having the chance to do so.

Naito:First having a go at changing your own environment while you are still young, is important. Additionally, while there have been various views expressed on gender in recent years, I think that we should keep in mind the existence of someone like Toshiko Yuasa. I think that we should be living in a world which affirms the attitude of sticking to one's beliefs regardless of gender.

Takeuchi:I often interview female scientists. Many of them seem to know about my attitudes towards women in advance through social media and so on. I was startled when I realized this and wondered why that was the case. It seems that because there are still few female scientists, some believe that they cannot protect themselves unless they investigate the way of thinking of the person they are going to be talking to. This kind of situation just shouldn’t be.

Naito:That’s not a good situation. As Mari Curie argued, diversity in the true sense of the word can only come about in a world where people are valued for their achievements and can play an active role, regardless of their gender.

Naito:Speaking of diversity, people being classified as either in the humanities or in the sciences is one issue related to that. In Japanese terms, I am a student of the humanities, but I did amateur radio when I was a junior high school student, and I was in the physics club when I was in high school. I also love Kodansha Bluebacks, series of books on the natural sciences published by Kodansha, and read Professor Takuji Tsuzuki’s book The Principle of Uncertainty. It looked like a difficult read, but when I opened it up, there was a picture depicting the cartoon Star of the Giants and explanations which likened the Vanishing Pitch to the concept of quantum space, which made me think about how interesting physics is. While I went on to study at the faculty of law in university, it might have been the case that I joined Hitachi because I like electrical and electric equipment. In terms of school entrance exam categories, I'm part of the humanities. But I am interested sciences. Many people in the sciences, however, think that people in the humanities wouldn’t understand the sciences, which makes me feel like there is a disconnect between the humanities and the sciences. There is also a separation between those who are into athletic activities and those who are into cultural activities. I don't think it's necessary to categorize people like that. I wonder why people want to separate themselves from others like this.

Takeuchi:As for the humanities and the sciences, in the case of Japan, I think the distinction is influenced by school entrance examinations. I think it is strange that the examined subjects differ in the first place. If you trace back where this all started, it was during the Meiji era. The distinction was made based on whether costs were to be incurred. Faculties that needed money for experiments and other such initiatives were classified as belonging to the sciences, and those that did not were classified as belonging to the humanities. As a result of that, the academic subjects tested during entrance examinations were divided up into those categories. This became entrenched and a peculiar system ended up being put in place in which high school education had students taking different academic paths accordingly.

The first thing I noticed when I studied abroad was the freedom students had to go back and forth between the sciences and the humanities. It doesn't make sense to have a someone studying economics using a computer to be placed into either of these groups. The boundary is vague and there is gradation. In Japan, the image people have is that there is a complete gap between the groups. I think that is strange.

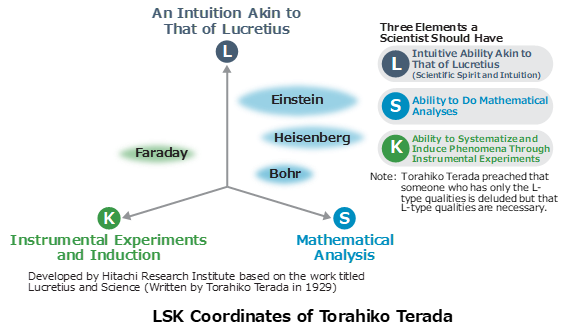

Naito:There is an essay by Torahiko Terada called Lucretius and Science (included in Torahiko Terada’s Essays Vol. 2, Iwanami Bunko). Titus Lucretius Carus*14 wrote an easy-to-understand poem about the Brownian motion and the concept of atoms, which ties in with modern science. In contrast, the tone in the West seemed to be that discussions of mere ideas without doing any mathematical analysis or having experiment-based proof could not constitute scientific endeavors. In the essay, Torahiko Terada explains the three elements that a scientist should possess: an Intuitive Ability Akin to That of Lucretius (L), the Ability to Do Mathematical Analyses (S), and the Ability to Systematize and Induce Phenomena Through Instrumental Experiments (K). Mathematical analysis and experimental proof are not enough for something to be called a science; science requires an intuitiveness that is akin to that of Titus Lucretius Carus.

When this concept is applied to the social sciences, which is the field of research conducted at Hitachi Research Institute, it is not enough to study elements like business models and economic theories and examine examples of success and failure through verification taking place during fieldwork. I think it is also necessary to have ideas about trends in the world and trends in terms of people’s values first and to have a way in which those ideas are verified. Torahiko Terada was a famous haiku poet, waka poet and essayist who studied under Soseki Natsume. I think he was exactly the kind of person who saw no barriers between the humanities and the sciences.

Takeuchi:A true person of culture. I thought it was interesting that Torahiko referred to Lucretius' intuition. When you think about the structure of the brain, intuitiveness is something akin to a gut feeling. In order to escape from predation, a living creature needs to be able to sense danger, and the brain must have a mechanism to determine instantaneously whether there is a danger present. As a living creature, it's natural to value your gut feelings when it comes to determining whether things are going to work out.

I suspect that great scientists are surprisingly obedient to their gut feelings. Before you think mathematically or do an experiment, start by accepting your feelings about whether a situation looks good or bad. During that process, try to think in theoretical terms using mathematical expressions and then attempt your experiment. There is an exquisite balance to be struck between those elements.

Naito:While specialized fields are obviously important, I think it's crucial to have an educated perspective, and broadly speaking, I think that learning history is important. We have much to learn from our past experiences and from the answers provided by our ancestors when it comes to various challenges; that is not only the case when it comes to correct answers but also when it comes to incorrect answers. We can't move on to the next step without knowing that. I feel that many excellent managers have a deep knowledge of not only their own country's history but also the history of the world, and that they stand on a solid foundation.

Takeuchi:The history that is taught in school is mainly memorized and people have been pointing out the harmful effects of doing things that way. On the other hand, some memorization is necessary, such as when it comes to the multiplication table. The multiplication table is not only convenient, but also important as a base for thinking about more advanced things. I don't mean to negate memorization skills, but we now have artificial intelligence available, so memorization-type skills are something that will end up being left to AI. The “ability to think” will become more and more important in the future, but if you are just studying by means of memorization all the time or have the habit of waiting for instructions before you do something, this ability will not develop itself. I believe that educators should adopt inquiry-based education systems which emphasize the process of “thinking” based on one's awareness of issues, interests, and concerns. There are statistics which show that memorized knowledge is largely forgotten after tests and exams. Meanwhile, students who continue to research things can acquire a lot of knowledge in the process and connect it all together organically. If we don't start with this kind of education in elementary school, I think that our country is going to end up in a tough situation.

Naito:What are the keywords we need to keep in mind when it comes to thinking about issues having to do with human resource development in the age of AI?

Takeuchi:One is “consciousness.” Current AI has no consciousness. But we do. Consciousness, however, is not something that is understood by neuroscience, so there is no definition for it. We cannot say for sure whether it’s there or not. Cats and mice may have consciousness. But do bees and ants? For now, AI seems to not demonstrate consciousness. Even if there is a faint cloud of consciousness present, there is a big difference between that and human consciousness.

That’s why we must be able to naturally distinguish between tasks that only a human being with consciousness can do, and tasks that an AI, which has no consciousness, can do with incredible speed and precision. As AI learns more and more about the vast amount of data from the past, humans need to be doing creative work to counter that.

AI-based shogi software is very good at the game itself, but it never feels enjoyment or frustration. Professional shogi players, on the other hand, carry on their shoulders the expectations of those around them, risk their own existence, and take on their opponents with a comprehensive consciousness. The same goes for artists, who are driven to stir the soul and give shape to that drive through their techniques. But an AI without a consciousness doesn't have that drive. Humans have ethical or emotional motivations. Wanting to have a good life, wanting to be happy, wanting one’s family to be happy, wanting one’s friends to be happy, wanting one’s company to be in a good situation, and wanting the world to be peaceful and prosperous. These modes of thought come from consciousness. I think that constitutes a significant difference between humans and AI.

Naito:It is important to create environments which serve to support such human consciousness. Digital technologies are certainly useful. My feeling is that a great expansion of uncharted territory has taken place. One example of a contribution by science and technology to culture is oil paint contained in tubes. Oil paint dries quickly and cannot be taken outside, so until oil paint contained in tubes was invented, the production of paintings took place exclusively in painting studios. However, the invention of paints contained in tubes made it possible to create paintings outdoors, which led to the success of the Impressionist movement. Likewise, it is important to think about what can be done with modern digital technologies.

Takeuchi:Some say that the digital world is getting closer and closer to reality, but reality is actually created by the brain in the first place. The brain uses information that is input through the eyes, ears, and other sensory organs to create the tilt, shape, and color of objects through simulations. We recognize the things our brains have created as the real world.

The sensory awareness that arises within our consciousness and the experiences which accompany that are called qualia in neuroscience. The detailed mechanisms that produce this effect, however, are unknown. For example, the color red refers to a wavelength of light that is around 700 nanometers in length, but an AI doesn't know what “reddish things” or “red images” captured by the brain are. So right from the start, there's a big difference between what reality is for humans and what reality is for AI.

Merging reality with digital technologies, if we think of the brain as a kind of computer, means, in a way, merging together the real world created by humans using the brain and the digital world that humans are trying to create using AI and computers. That’s what I think.

Naito:The Doppler effect of light suddenly comes to mind. It is said that objects which emit light appear bluish when approaching and reddish when moving away. Fundamental questions come up here: what is meant by “red” and “blue” in this context? What do these terms mean when you think more deeply about them? I would guess we’re talking about thinking of wavelengths of light as meaningful “colors.” There is a theory originating from Newton that rainbows are seven colors, but I remember reading description in the work Azuma Kagami (“Mirror of the East”) “a five-color rainbow appeared.” It’s very interesting to think about what constitutes color.

Takeuchi:Different environments may come with different languages and worldviews, but the basic structure of the brain is common to all humans. I think as far as we can tell, there probably exists shared unconscious akin to Carl Gustav Jung’s collective unconscious. That must be found at the root of culture, so I think that it will probably serve as an important element going forward when it comes to contemplating the merging of the real and digital worlds.

Naito:There are still many areas where research should be taking place. AI is great, but we hear a lot about things that only humans can do. I feel encouraged by your specific comments.

Lastly, do you have any requests of or advice for the Hitachi Research Institute, a thinktank dedicated to the social sciences?

Takeuchi:I am now involved in educational activities, and I am concerned that Japanese education is more warped than the systems found in the rest of the world. Junior high school entrance exams put things into overdrive and students have to solve difficult and strange questions. More and more schools are using English as a test subject not only for individuals returning to Japan from abroad, but also for students taking the general school entrance exams. Some junior high school entrance exams require students to memorize words which appear in the first grade of the Eiken English language proficiency test. It's strange to force kids to memorize things even if the things they are memorizing don’t match where they are in terms of their own brain development.

We rose up against this and are currently implementing an inquiry-based education program that fosters critical thinking and creativity. People who can think for themselves will be able to use AI well even when the age of AI comes. Even if people can memorize a lot of things, our country will find itself in dire straits if we find that people have become unable to think for themselves. It is difficult to change this situation through the field of education alone. I would appreciate it if you could go about proposing ways in which we could reform things when it comes to our social systems.

Naito:I think we as adults are also very responsible for the problems that affect the future of our children. I think that responding to the educational activities that teachers are working hard on is an important role for society at large.

I have often said that innovation is a combination of existing knowledge, and that working with the stance that there may be combinations that we have not yet created, is something that can serve as catalysts for innovation. For this reason, I believe that we need a variety of perspectives, and it was very meaningful to hear your specialized point of view about the history of science, something which is not our specialization. Thank you very much for your time today.

*This interview was held with physical distancing measures in place.

Geniuses found throughout the history of science achieved great results by carrying out their research with a solid will and passion. But, we have recognized once again, that it is important to create time and environments in which people can think carefully in order to cultivate the kind of intuitive abilities that ought to be characteristic of scientists as pointed out by Torahiko Terada. That not only serves as a source of innovation, but also leaders to greater diversity. Mr. Takeuchi also pointed out the importance of education which fosters critical thinking and creativity. I strongly felt all the more that the “ability to think” for oneself and ultimately, people are crucial elements as we see AI merge further with our economies and societies.

Osamu Naito (Former Chairman of Hitachi Research Institute)