Digital technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) are being increasingly utilized in the bio sector, propelling biotechnologies from foundational research into practical applications across society. The field is advancing toward global problem-solving, from innovations in biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy that enhance well-being to industrial applications of microorganisms that address planetary boundaries and support a circular economy.

In our 2018 publication of Hitachi Souken Journal, we explored the theme of “Accelerating Industrial Innovation through Biodata Utilization.” At that time, the DNA*1 -editing technology CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, CRISPR Associated Protein 9) was becoming operational, spotlighting the value of biodata and generating considerable interest in its various industrial applications. Six years on, biotechnologies have advanced from healthcare into industrial applications, with practical implementations now underway.

In this report, we examine the current state of biotechnologies and their industrial applications, exploring the future society that is being pioneered by the social and industrial transformation through biotechnology (Biotechnological Transformation: BX*2 ).

In 2012, the DNA-editing technology CRISPR/Cas9 was introduced, significantly advancing the field of bioresearch. Unlike traditional trial-and-error research methods, this technology enabled planned design, control, and manipulation of DNA sequences. When we explored “Accelerating Industrial Innovation through Biodata Utilization” in our 2018 Hitachi Souken Journal feature, studies involving genetically modified microorganisms, plants, and animals using this DNA-editing technology were already being actively published.

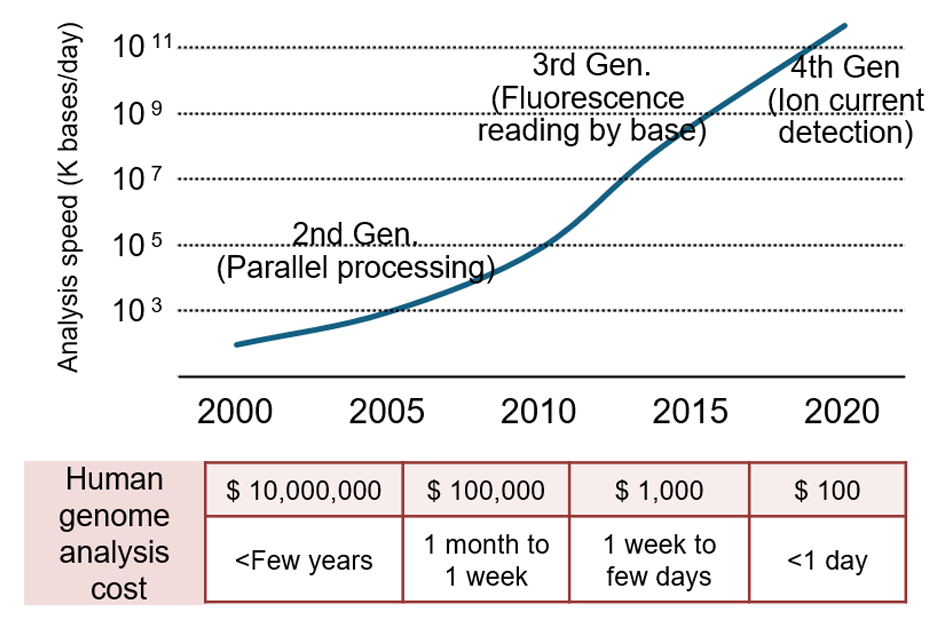

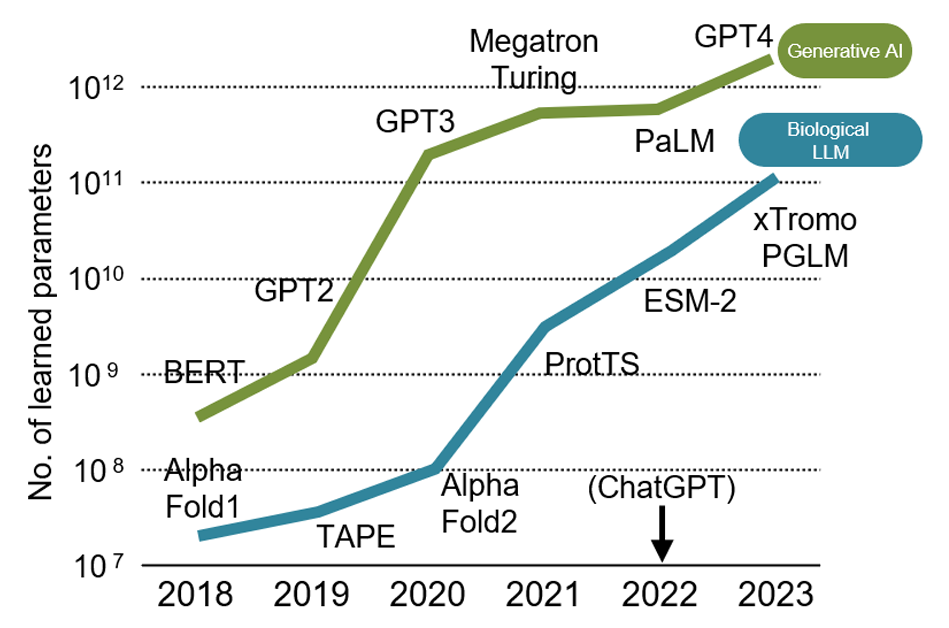

In the six years since, biotechnologies have progressed beyond research to practical and social applications, spurred on by new digital advancements and growing social demands. For example, in bio-measurement technology, sequencers that analyze DNA base sequences have continually improved, evolving from fluorescence-based measurement to electric-current-based technologies, enabling rapid reading of long base sequences. Today, this allows for the human genome to be sequenced affordably and quickly, within a single day at a cost of just $100 (Fig. 1). Additionally, advances in digital technology, such as deep learning and generative artificial intelligence (AI), have broadened applications in the bio sector. Specifically, biochemical data such as amino acid sequences and protein structures, along with academic literature, are now used to train large language models (LLMs) specialized for biochemistry. Generative AI based on these biochemistry-focused LLMs has reached a practical level for researchers where it can read genomic information as a language and interpret the meaning and functions of genes contained in the genome (Fig. 2). Societal demands are also accelerating the implementation of biotechnologies. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the urgent need for mass-produced vaccines led to the rapid development of messenger RNA (mRNA)*3 vaccines, with rollout beginning by late 2020. Approval processes that normally take years in the U.S. were fast-tracked in less than a year due to the pressing social need during the pandemic. Currently, biotechnology is undergoing transformation through digital × bio applications, primarily in healthcare, with the potential for BX to expand across various industrial sectors to address global challenges.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 1: Changes in DNA sequencer analysis speed

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 2: Changes in the number of LLM learning parameters

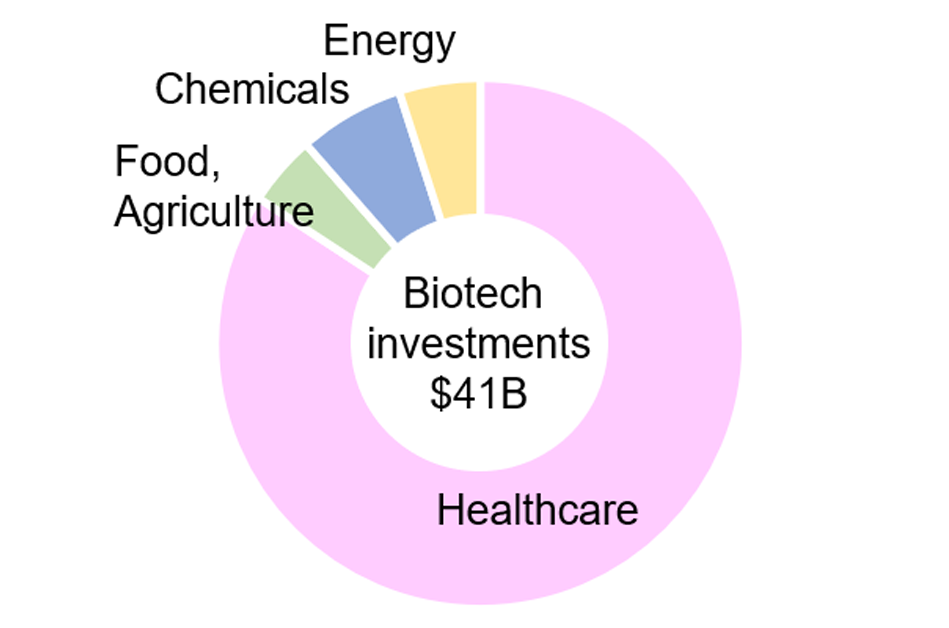

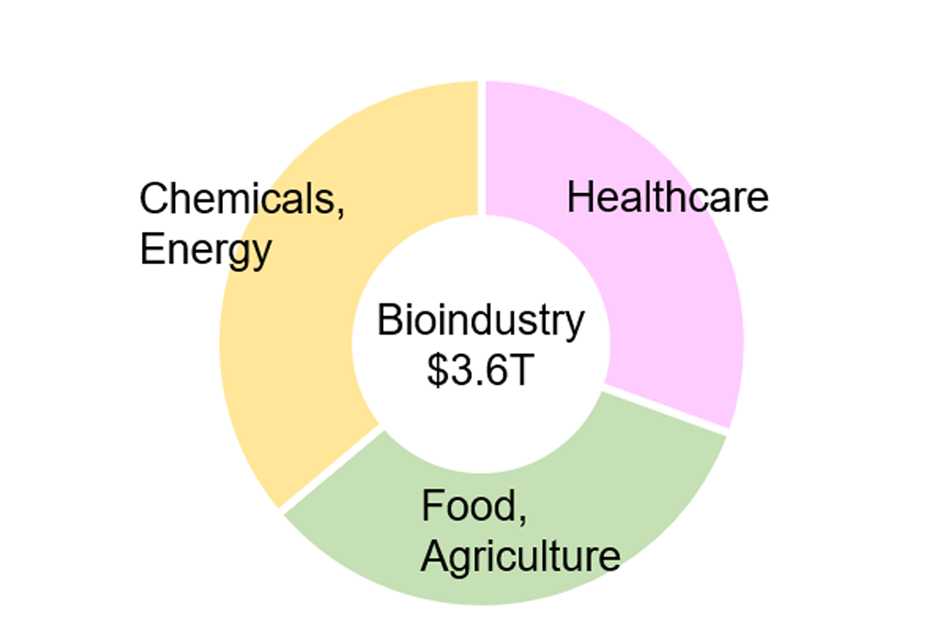

Currently, venture capital investment in biotech startups is concentrated in the healthcare sector (Fig. 3). However, investment is foreseen to expand into sectors such as food, agriculture, chemicals, and energy. This trend is reflected in the projected growth of the bioindustry market, which, by 2030 and beyond, is expected to reach a comparable scale across healthcare, food and agriculture, and chemicals and energy (Fig. 4).

In fields such as biopharmaceuticals, where new added value is generated, active investment is being made, and the use of digital technologies, including generative AI, are significantly reducing research and development timelines, driving practical implementation forward. On the other hand, in sectors aimed at replacing existing products (e.g., petrochemical products), such as chemical materials and energy or fuel, there is a demand for products at the same or lower cost than existing ones, necessitating further innovation to achieve mass production and cost reductions.

In Chapters 2 and onward, we will review the technological innovations brought by digital × bio advancements in healthcare and explore the potential for bio-manufacturing applications across other industrial sectors, including chemical materials, food, agriculture, and energy.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 3: Investments in biotech startups (2022)

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 4: Global bioindustry market forecast (2030)

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the social implementation of mRNA vaccines, but it took 30 years of foundational research before they became practical. The potential to use RNA as a drug was first identified in the late 1980s, with the first clinical trial of an mRNA vaccine for influenza taking place 25 years later. By 2020, several mRNA vaccine candidates had been developed, though large-scale trials had not yet occurred. However, the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 fast-tracked vaccine development, allowing Moderna to progress from prototyping to human trials within ten weeks and BioNTech, in collaboration with Pfizer, to obtain emergency use approval just under eight months after starting trials.

Compared to the lengthy period from basic to applied research, the rapid move to mass-produce vaccines following the COVID-19 pandemic as achieved through the synergy of digital technologies for mRNA design and biotechnologies for vaccine production. Traditional influenza vaccines are made by growing viruses in specialized cells such as chicken eggs, which is time- and labor-intensive. In contrast, mRNA vaccines involve first analyzing the virus's genetic code to identify effective genetic sequences, designing genes for vaccine, and then using bioreactors to produce the mRNA vaccines in large quantities without needing to cultivate actual viruses in cells. This approach enables vaccine design and production from genetic information alone and allows for immediate modifications if the virus mutates. The improved performance of DNA sequencers, advancements in biochemical LLMs, genetic databases, simulations, and vaccine production technologies, i.e., the combination of digital and biotechnologies made rapid mRNA vaccine implementation possible.

Not limited to vaccine development, traditional drug development has heavily relied on trial-and-error testing of various compounds and chemical reactions, leading to high investments and low success rates. The digital-driven drug development approach, demonstrated with the mRNA vaccines, is expected to reduce development time, lower investments, and increase success rates by using genetic data.

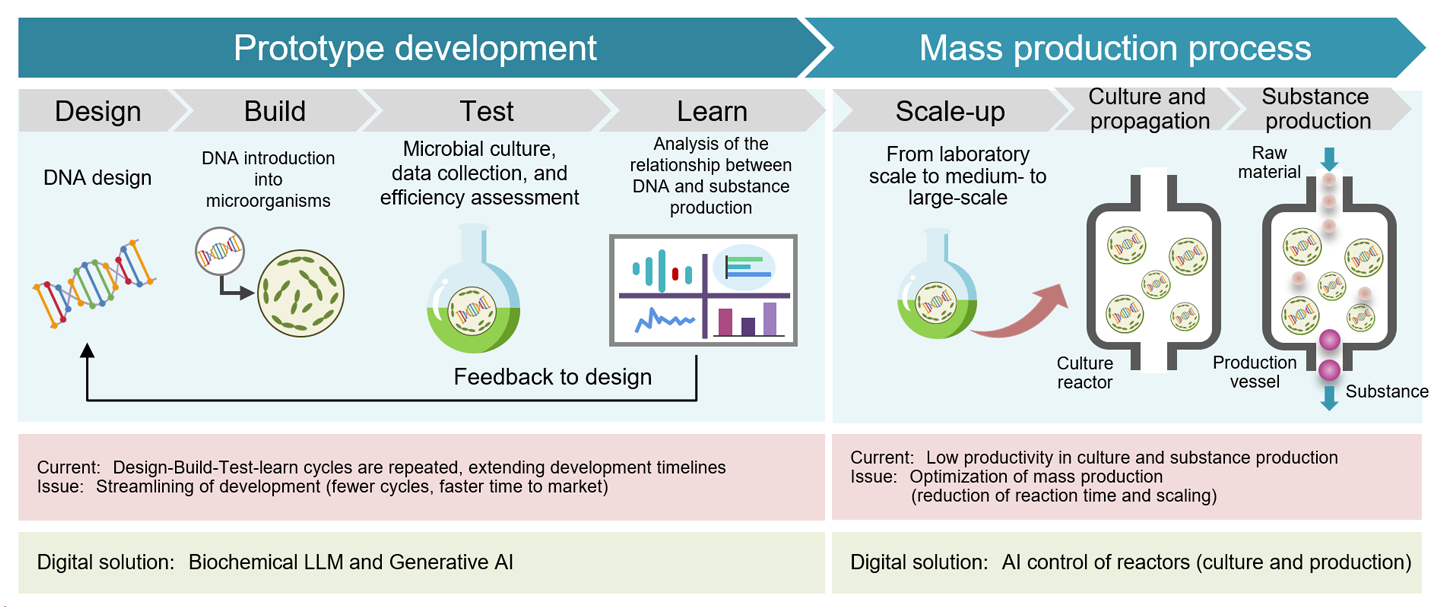

The creation of a wide range of products using various biotechnologies is called bio-manufacturing, with practical applications emerging primarily in healthcare, as mentioned above. In addition to directly utilizing amplified genes, as in mRNA vaccines, bio-manufacturing also involves designing and modifying gene-coding DNA (i.e., the base sequence) to create new microorganisms that produce useful substances—a method employed in numerous industries. This bio-manufacturing process includes two phases: "prototype development," where new microbes are created through DNA design and modification, and "mass production," where these microbes are grown to generate the desired materials in large quantities (Fig. 5).

Prototype development involves repeated experimental cycles of DNA "design," "build," "test," and "learn." During the "design" phase, DNA structures (gene functions and base sequences) necessary for a new organism to produce valuable substances are evaluated. "Build" incorporates new DNA into microorganisms, while "test" involves cultivating these microbes, collecting data on their proliferation, and assessing their substance production efficiency. In the "learn" phase, researchers analyze the relationship between DNA design and substance production, then feed insights back into "design" for improvement.

Currently, multiple cycles of this process are often required to achieve target microorganisms, extending development timelines. Reducing these cycles to shorten development time is a key challenge in prototype development.

Biochemical LLMs address this challenge by increasing the accuracy of AI predictions as more training data accumulate. This reduces the time spent on "design" and increases success rates during "test." Furthermore, data accumulated from the "learn" phase can better inform subsequent "design" steps, and the "build" with AI-enhanced culturing controls and automation improves experimental efficiency. Ultimately, this reduces the number of experimental cycles, shortening development timelines and lowering investment costs.

For instance, Ginkgo Bioworks (U.S.) stores experimental data from its labs on Google Cloud, aiming to develop its own LLM. Evozyne (U.S.) uses NVIDIA's BioNeMo service, a biochemical LLM, to shorten the time required for large-scale protein model training from several months to just a week.

During the mass production phase, microbes are cultivated and used to produce useful substances in large quantities. Challenges include unexpected microbial contamination or production of harmful substances, which can reduce microbial populations and impair production efficiency. Solutions involve optimally controlling conditions within microbial bioreactors (vessels for culturing or generating desired substances) through digital technology. Specifically, sensors measure environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, oxygen levels, pH, stirring speed, feedstock input, and product discharge rates) in real time in accordance with growth progress and production levels, while AI helps adjust conditions to optimize production and quality.

Pow.Bio (U.S.) separates reactors into culture and production vessels, where AI dynamically adjusts optimal conditions for each vessel to stabilize product quality, boosting productivity by 2-5 times.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 5: Challenges and digital countermeasures in the bio-manufacturing process

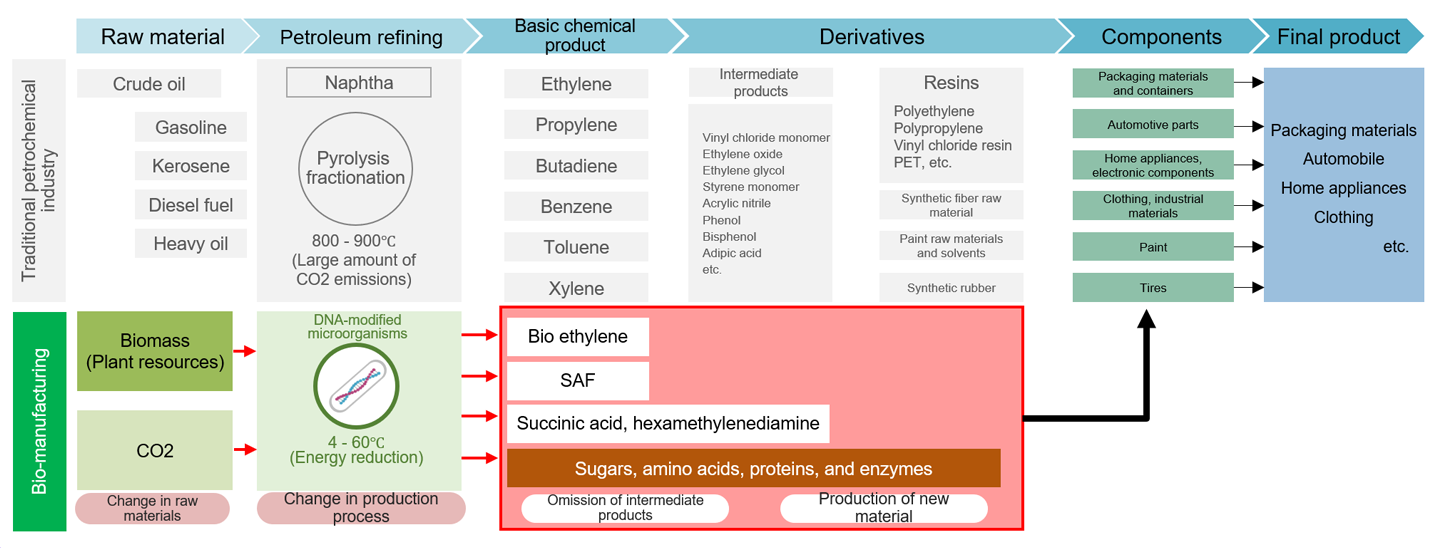

The widespread social implementation of bio-manufacturing is anticipated to significantly transform the structure of the manufacturing supply chain (Fig. 6). Traditional manufacturing that uses petroleum as raw material involves extracting crude oil, refining it into naphtha and fuel, and then breaking down the naphtha at high temperatures (above 800°C) to produce basic chemicals and derivatives. These chemicals are then processed into components and assembled into final products. In contrast, bio-manufacturing uses biomass (organic resources derived from biological sources, excluding fossil resources) or carbon dioxide (CO₂) as raw materials. Microorganisms metabolize these materials through processes like fermentation to produce chemicals. Since the bio-manufacturing process generally requires only room-temperature conditions, it can drastically reduce energy consumption. Additionally, bio-manufacturing enables direct production of desired chemicals from raw materials, bypassing intermediate products and shortening the supply chain, which also helps reduce CO₂ emissions.

Thus, bio-manufacturing fundamentally changes the supply chain player structure by altering the sources of raw materials and the processes for generating intermediate products and materials. For instance, the production of raw materials shifts from oil majors to grain majors, and chemical manufacturing transitions from traditional chemical companies to bio firms. In the bio-manufacturing industry, horizontal specialization is also expected to increase due to the high-value assets and development investments requirements. To control development costs, bio companies are likely to collaborate with innovation hubs and focus on R&D and design. Experiment-intensive tasks requiring substantial investment in laboratory equipment and experimental organisms will be outsourced to specialized contract research organizations (CROs), which handle research requests from multiple companies. In mass production, shorter processes and reduced energy requirements mean that large-scale plant infrastructure is no longer necessary, paving the way for the rise of contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) to play a key role in the supply chain.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 6. Supply chain for petrochemical and bio-manufacturing

Bio-manufacturing, initially applied in pharmaceuticals and healthcare, is also gaining traction in other industrial sectors. In the petrochemical industry, resource-rich countries and emerging economies are entering the field of basic chemical production, challenging non-resource nations in terms of competitiveness due to the costs of purchasing and transporting petroleum, the raw material. Additionally, the steel industry is exploring environmental measures to reduce CO₂ emissions due to the significant amounts produced in steelmaking processes. Given these developments, industries such as chemicals and steel have begun adopting biotechnologies.

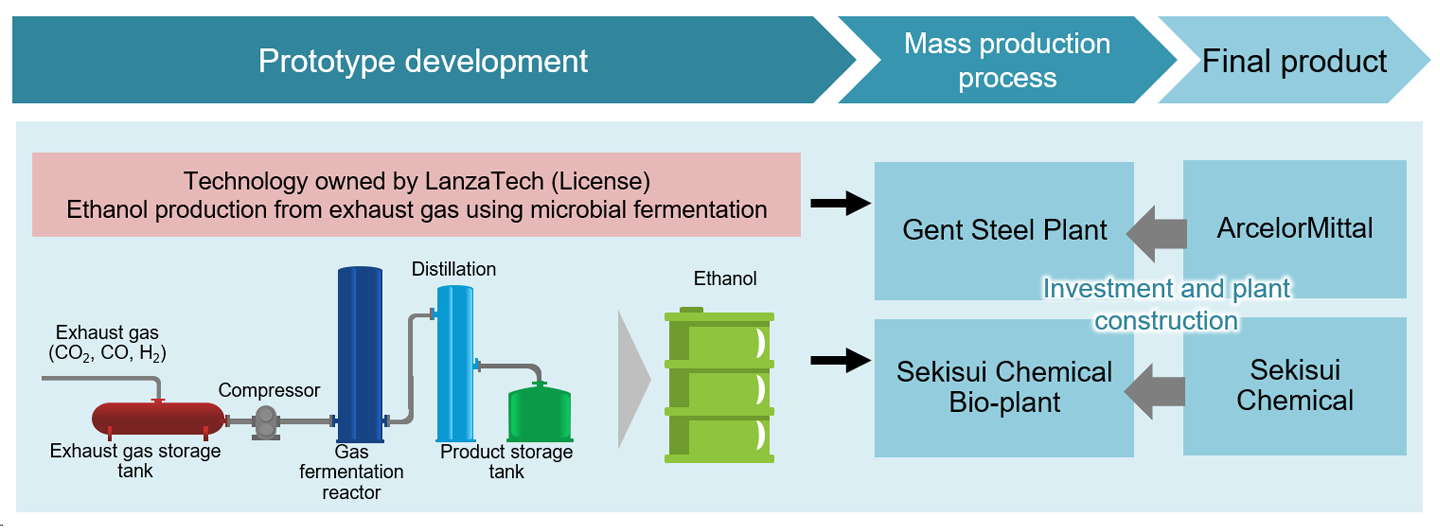

LanzaTech, for example, has developed technology using genetically modified microorganisms to produce bioethanol from CO₂, which it licenses to manufacturing companies to advance the social implementation of biotechnology (Fig. 7). Sekisui Chemical, a chemical manufacturer, operates a bio-plant under license from LanzaTech. Meanwhile, steelmaker ArcelorMittal has set up a plant in its steel factory to capture CO₂ emissions and produce bioethanol using LanzaTech’s technology. Thus, efforts to operate bio-manufacturing are becoming more prominent across various manufacturing fields.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 7: Manufacturing industry adopting bio-manufacturing with microbial licenses

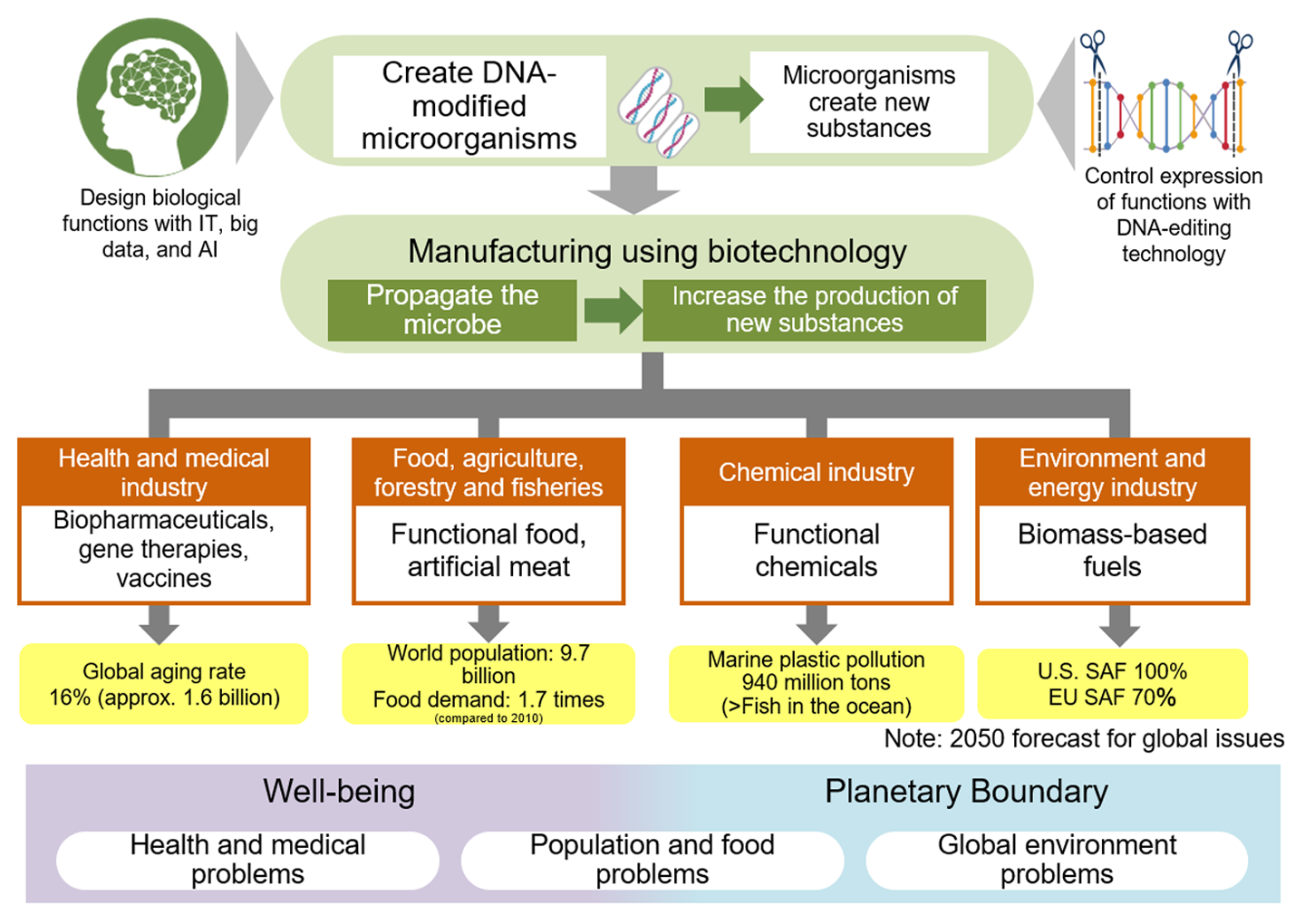

As bio-manufacturing becomes widely spread into our economy, industry, society, and daily lives, it is expected to contribute to solving global challenges, such as advancing healthcare, improving well-being through health and food safety, and addressing planetary boundaries through biofuels and bioplastics. This shift could significantly influence government policies on industry, the environment, as well as energy and resource security, fundamentally changing the supply chain, restructuring industries, and impacting the economy and industry as a whole (Fig. 8).

In terms of well-being, bio-manufacturing can help address challenges within the medical, health, and food sectors. By 2050, the global population is expected to reach 9.7 billion, with an estimated 16% over the age of 65 (UN data*4). In an aging world, extending healthy life expectancy becomes a priority, calling for advancements in biopharmaceuticals, gene therapy, health-promoting microbiomes (microorganisms in the human body), and other biotechnologies. Additionally, food demand is projected to increase 1.7 times between 2010 and 2050 (Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries*5), raising concerns over food distribution and shortages. Biotechnology solutions like artificial meat and functional foods are anticipated to help address these issues.

Regarding planetary boundaries, bio-manufacturing can support solutions within the chemical, environmental, and energy sectors. With greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, like CO₂, accelerating global warming, reducing GHG emissions has become critical. By using biomass and CO₂ as raw materials, bio-manufacturing offers an effective means of addressing climate change. For example, biomass-based fuels, such as Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), derived from biomass, are being implemented as a countermeasure to global warming.

Another serious environmental issue, marine plastic pollution, is projected to worsen significantly worldwide, with an estimated 940 million tons of plastic in the ocean by 2050—exceeding the total weight of fish (World Economic Forum*6). The development and spread of biodegradable plastics that microorganisms can break down are seen as essential steps forward.

These solutions to global issues related to well-being and planetary boundaries through bio-manufacturing could also influence national security and industrial competitiveness. As bio-resources replace petroleum as the primary raw material and energy source, oil-producing nations may see a reduction in their national power, while the influence of grain-exporting countries rises. Additionally, developing countries, rich in genomic data from previously unknown microorganisms, could leverage this data to enhance their standing in the international community. Japan, with its abundant water and forest resources, is well-positioned to strengthen its industrial competitiveness through manufacturing using biotechnology.

Source: Prepared by HRI from various materials

Figure 8. Bio-manufacturing and the solution of global issues

Two main challenges remain for the full-scale social implementation of bio-manufacturing. The first is establishing further advancements in technology. Reducing the price of bio-based products will require shortening and streamlining research and development timelines, increasing productivity for mass production, and lowering production costs. The second challenge involves raising awareness and developing regulations and guidelines for the use of biotechnology. There is not yet widespread public acceptance of new organisms created through DNA editing. Therefore, it is necessary to establish regulations and promote social acceptance through public awareness efforts. Additionally, proactive risk prevention and avoidance measures must be taken to mitigate potential biohazard risks.

Assuming that BX (Biotechnological Transformation) will become the third pillar of industry, following DX (Digital Transformation) and GX (Green Transformation), we will continue advancing research in the bio sector.

Masayuki Miyazaki, Ph.D. (Engineering)

Chief Researcher, 3rd Research Department, Hitachi Research Institute

Joined Hitachi, Ltd. and engaged in research and development of semiconductors, networks, and IoT. Assumed his current position after working in the R&D Group. In addition to biotechnology, he is currently researching technical strategies in the fields of digital, security, and innovation.

Hiroshi Nishimura

Associate Senior Researcher, Industry Research Group, 3rd Research Department, Hitachi Research Institute

He has been engaged in manufacturing and supply chain DX and technical strategy formulation. He has been in his current position since 2024. His recent research interests include biotechnology, GX, regional economy, and generative AI.

Author’s Introduction

Masayuki Miyazaki

Chief Researcher,

3rd Research Department

Hiroshi Nishimura

Associate Senior Researcher,

Industry Research Group,

3rd Research Department

The Prospects of a Society Pioneered by Biotechnological Transformation

We provide you with the latest information on HRI‘s periodicals, such as our journal and economic forecasts, as well as reports, interviews, columns, and other information based on our research activities.

Hitachi Research Institute welcomes questions, consultations, and inquiries related to articles published in the "Hitachi Souken" Journal through our contact form.